|

| Image: A Schematic Outline of the Cosmic History - Credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team |

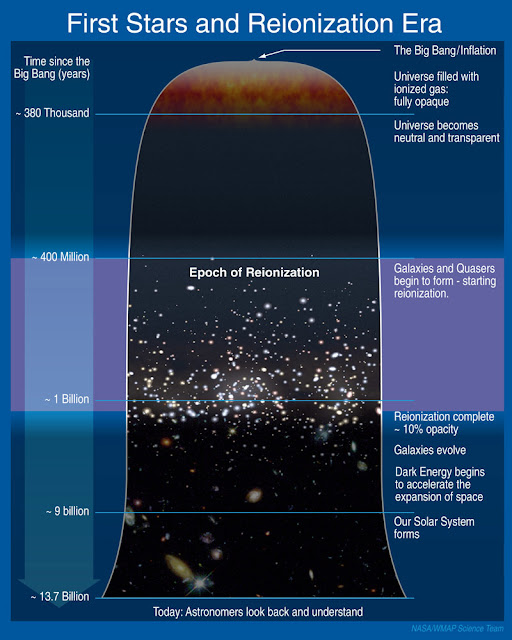

The epoch of reionisation and the emergence of the universe from the cosmic dark ages is a subject of intense study in modern cosmology.

As baryonic matter began to collapse around initial fluctuations in the dark matter (DM) density seeded by inflation, the earliest galaxies in our universe began to form. These structures, perhaps accompanied by other sources, eventually began to emit ionising radiation, creating local patches of fully ionised hydrogen gas around them. These patches ultimately grew to encompass the entire universe, leading to the fully ionised intergalactic medium (IGM) that we observe today.

While the process of reionisation is broadly understood, the exact details of how and when reionisation occurred are still somewhat unclear.

Dark matter annihilation or decay could have a significant impact on the ionisation and thermal history of the universe.

In a recent paper (Liu et al. 2016) the authors study the potential contribution of dark matter annihilation (s-wave- or p-wave-dominated) or decay to cosmic reionisation, via the production of electrons, positrons and photons.

They map out the possible perturbations to the ionisation and thermal histories of the universe due to dark matter processes, over a broad range of velocity-averaged annihilation cross-sections/decay lifetimes and dark matter masses.

They find that for dark matter models that are consistent with experimental constraints, a contribution of more than 10% to the ionisation fraction at reionisation is disallowed for all annihilation scenarios.

Such a contribution is possible only for decays into electron/positron pairs, for light dark matter with mass mχ ≲ 100 MeV, and a decay lifetime τχ ∼1024−1025 s.

Liu et al. 2016 (preprint) - The Darkest Hour Before Dawn: Contributions to Cosmic Reionisation from Dark Matter Annihilation and Decay - (arXiv)

Comments

Post a Comment