|

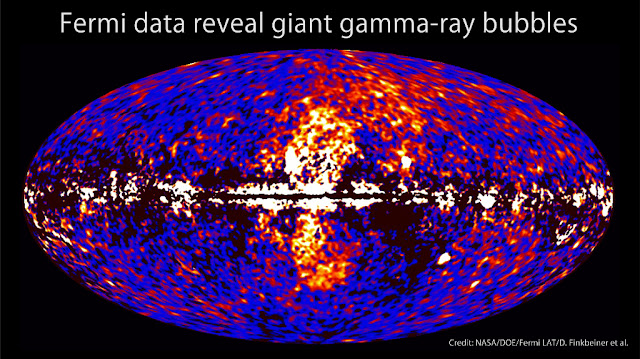

| Image: A giant gamma-ray structure was discovered in 2010 by processing Fermi all-sky data at energies from 1 to 10 billion electron volts, shown here. The dumbbell-shaped feature (center) emerges from the galactic center and extends 50 degrees north and south from the plane of the Milky Way, spanning the sky from the constellation Virgo to the constellation Grus. Credits: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT/D. Finkbeiner et al. |

At a time when our earliest human ancestors mastered walking upright the heart of our Milky Way galaxy underwent a titanic eruption, driving gases and other material outward at 2 million miles per hour.

Now, at least 2 million years later, astronomers are witnessing the aftermath of the explosion: billowing clouds of gas towering about 30,000 light-years above and below the plane of our galaxy.

The enormous structure was discovered in 2010 as a gamma-ray glow on the sky in the direction of the galactic center. Astronomers have since observed the balloon-like features in X-rays and radio waves, but needed NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to measure for the first time the velocity and composition of the mystery lobes.

The giant lobes, dubbed Fermi Bubbles, initially were spotted using NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The detection of high-energy gamma rays suggested that a violent event in the galaxy's core violently launched energized gas into space.

|

| Image: Hubble maps velocity and composition of mysterious lobes expanding from our galaxy. Credits: NASA, ESA, A. Fox and A. Feild (STScI) |

The gas on the side of the bubble closer to Earth is moving towards us and the gas on the far side is travelling away. The gas is rushing from the galactic center at roughly 2 million miles an hour, or 3 million kilometers an hour.

The material being swept up in the gaseous cloud is composed by silicon, carbon, and aluminum, indicating that the gas is enriched in the heavy elements produced inside stars and represents the ancient remnants of star formation.

The temperature of the gas at approximately 17,500 degrees Fahrenheit, which is much cooler than most of the super-hot gas in the outflow, thought to be at about 18 million degrees Fahrenheit.

One possible cause for the outflows is a star-making frenzy near the galactic center that produces supernovas which blow out gas. Another scenario is a star or a group of stars falling onto the Milky Way's super-massive black hole. When that happens, gas superheated by the black hole is ejected deep into space.

Because the bubbles are young compared to the age of our galaxy, and believed to be a short-lived phenomenon, the bubbles may be evidence for a repeating event in the Milky Way's history. Whatever the trigger is, it likely occurs episodically, perhaps only when the black hole gobbles up a concentration of material.

Galactic winds are common in star-forming galaxies, such as M82, which is furiously making stars in its core. Although the Milky Way overall currently produces a moderate one to two stars a year, there is a high concentration of star formation close to the core of the galaxy.

Source:

- Hubble Discovers That Milky Way Core Drives Wind at 2 Million Miles Per Hour - (NASA)

Comments

Post a Comment