|

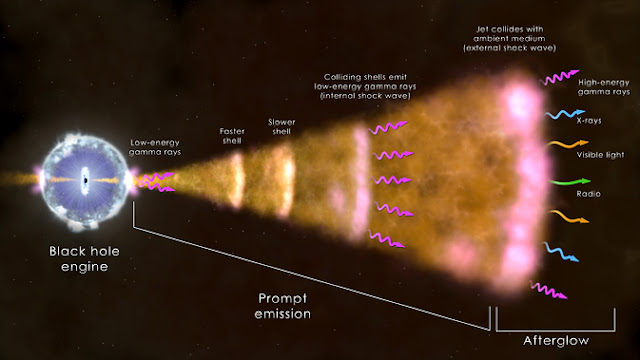

| Image: In the most common type of gamma-ray burst, illustrated here, a dying massive star forms a black hole (left), which drives a particle jet into space. Light across the spectrum arises from hot gas near the black hole, collisions within the jet, and from the jet's interaction with its surroundings. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center |

Astrophysical explosions and jets generate shock waves, which produce radiation. Their radiative properties are determined by the dissipation mechanism that sustains the velocity jump in the shock and by its ability to generate nonthermal particles.

A recent paper (Beloborodov 2016) examines the mechanism of internal shocks in gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) that occur before the GRB jets become transparent to radiation. The approach and some of the results may also be of interest for other explosions, e.g. in novae or supernovae.

A recent paper (Beloborodov 2016) examines the mechanism of internal shocks in gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) that occur before the GRB jets become transparent to radiation. The approach and some of the results may also be of interest for other explosions, e.g. in novae or supernovae.

Sub-photospheric shocks can produce neutrino emission and affect the observed photospheric radiation from the explosion. Shocks develop from internal compressive waves and can be of different types depending on the composition of the flow:

- Shocks in 'photon gas' with small plasma inertial mass have a unique structure determined by the 'force-free' condition -- zero radiation flux in the plasma rest frame. Radiation dominance over plasma inertia suppresses formation of collisionless shocks mediated by collective electromagnetic fields.

- Strong collisionless subshocks develop in the opaque flow if it is sufficiently magnetized. The author evaluates the critical magnetization for this to happen. The collisionless subshock is embedded in a thicker radiation-mediated shock structure.

- Shocks in outflows carrying a free neutron component involve dissipation through nuclear collisions. At large optical depths, the shock thickness is comparable to the neutron free path, with an embedded radiation-mediated or collisionless subshock.

The author finds that sub-photospheric shocks are capable of generating high-energy particles and boosting the photon number carried by the outflow, and that the shock type changes as the outflow expands toward its photosphere. Strong e± pair creation occurs as the shock wave approaches the photosphere. Then the e±-dressed shock carries the photosphere with it up to two decades in radius, producing a strong observed pulse of nonthermal photospheric radiation.

- Beloborodov 2016 (preprint) - Sub-photospheric shocks in relativistic explosions - (arXiv)

Comments

Post a Comment